Well, sometimes it can be easy to forget what economics is all about. According to economic theory, our wants are unlimited yet resources are scarce. Economics is the answer to understanding and perhaps even managing scarcity in a world of rational consumers. This article covers popular economics one would expect an educational institute to have in its curriculum; the kind of economics of which I am not particularly fond.

Yes, homo-economicus have an unreliable view of the world and rationality. But, companies, governments and other econs use this brand of economics to interact with markets, introduce policies and sign trade agreements. There are other schools of economics that try to model actual behavior rather than making rational models fit irrational people. This wall of text is not about behavioural economics or another school that adopts pluralism in economics. That may be a future article.

The must-knows

The topics are vast; I’ll add an outline for what you “must” know about microeconomics and macroeconomics. This will lay a foundation for reading any sort of economics book, a casual economist article or conducting further research.

Microeconomic Outline

Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) shows the various amounts of two goods that can be produced. This illustrates opportunity costs and trade-offs. A simple cake factory, for example, cannot make both cheesecakes and cupcakes at the same time. They must produce one or the other or reconfigure the machine and make both at different times, thus losing time and making less of each. Generally, it makes more sense to specialise than make various things because of associated costs.

Supply and demand is a bit intuitive. The law of demand states holding all else constant, if the price of a product falls, the quantity demanded will increase and vice versa. Tip: Ceteris Paribus is a fancy word for holding everything constant. Likewise, ceteris paribus if supply increases then prices should fall. Unfortunately, markets are dynamic and people must account for dynamic complexity rather than holding things constant.

Elasticity is the sensitivity of quantity demanded in response to changing prices. While most people will use the term elasticity, they actually mean price elasticity of demand. It is measured by something called the midpoint method. Elastic goods are sensitive to price changes. You may not purchase ketchup if it increased slightly in price; you might purchase a substitute instead. Inelastic goods are not as sensitive to price changes. An example is a medication (the reason big pharma can charge Americans so much for meds). Cross-elasticity is the changes in quantity demanded because of the price of another good; usually something complementary such as burgers and buns. Finally, there too is income elasticity which is the change in quantity demanded based on income. This is often used to determine whether something is a luxury or an inferior good. Bonus: Something perfectly elastic has demand perfectly tied to the price. A change in price could create infinite demand or demolish it completely. I believe money is a good example. If you could buy $1.00 for $0.99 there would be infinite demand; however, nobody would buy a $1.00 for $1.01.

Consumer and Producer Surplus. In layperson terms, a surplus is the amount of unused value left in a market (or for an individual). For example if I was willing to pay $50 for a book but purchased it for $20, the consumer surplus would be $30. Most companies try to capture all available consumer surplus. However, prices are usually the same for everyone, yet people value things differently. Hence there is always some leftover surplus in the market. Bonus: New-school companies like Amazon actually leave a lot of surplus in the market. It does not make economic sense but marketing sense. You’re satisfied when purchasing something worth $50, for $45. But, if you purchase something worth $50 for $30 you’ll tell friends and become a loyal promoter for the company. In this case, it is possible that the company might put downward pressure on its suppliers in order to deliver lower prices. Until there are no suppliers and competitors left and the company is perfectly horizontally and vertically integrated. They might even be the only employer left for a lot of people so they can set prices not only for products but for wages too! This is why people accept government intervention, to save us from dystopia.

Price Controls and Quotas – These take form usually as a new tax or a subsidy. They create something called deadweight loss. This is the surplus that neither the producer or the consumer could acquire. Conceptualise it by thinking about the price of candy which costs $1.00. After a tax is levied upon the candy the price increases to $1.20. This decreases the quantity demanded and that $0.20 did not actually add to the producer surplus (nor the consumer surplus). Are subsidies and price controls horrible? It depends; if the social, environmental or other benefits outweigh the deadweight loss then it was a good idea. The tax on cigarettes, for example, is a great idea. Since cigarettes are somewhat inelastic the tax burden is usually paid by the consumer, thus deterring some smokers. The taxes collected can be used to treat people with increased risk of cancer but also to build hospitals and schools which benefit everybody.

Perfect competition, Monopoly, Oligopoly and Monopolistic competition. People generally understand the terms monopoly and oligopoly. A monopoly might not necessarily mean one company exists in the market but that is often the scenario. It has to do with something called market power which means their ability to raise prices and remain the price-maker. People dislike monopolists since they can produce goods at their profit-maximising quantity of output which inherently creates a producer surplus. Most governments control or create monopolies. They control ones that are generally harmful to society while creating others that improve efficiency. A natural monopoly would be the power lines or water pipes. It makes no sense for each provider to build their own and it is ideal for one firm, usually the government to control it. On the other end of the spectrum is perfect competition. When many producers offer products consumers regard as equivalent or identical they are generally in a perfectly competitive market. In such a market all participants are price-takers. Commodity markets can be perfectly competitive. The markets we are familiar with (household names) are neither of the above. They are something called monopolistic competition, where each producer has some power to set prices by offering differentiated products. These products may be similar but consumers consider them non-identical. A firm can create differentiation in many ways such as catering to different tastes, location, quality or simply by advertising. Consumers are assumed rational but they can be swayed by advertising and brand names into making inefficient purchasing decisions.

Costs and decision making; people should not produce anything once the marginal cost is higher than the marginal benefit. Marginal cost is the cost of producing one additional unit; likewise, the marginal benefit is the money from selling one additional unit. This makes sense because once something costs more to make than sell, it is unprofitable. Bitcoin miners may stop mining coins once it costs more in electricity than the fee they receive (Bitcoin mining gets progressively harder). When firms willingly sell something for less than cost; it is usually part of a larger profit-producing strategy. While on topic remember that economic profit is different from an accounting profit. An accounting profit is simply revenue less expenses. Economic profit is revenue less explicit and implicit costs (revenue – (expenses + opportunity costs). Opportunity costs are the next best alternative for your time (and money). For example, running a cafe that earns $20,000 annually in profit might be an accounting profit, however, if you can earn $50,000 as a barista (elsewhere) you have made a -$30,000 economic loss.

Macroeconomic Outline

Hey, if you’re still here then you must be quite dedicated to the topic.

Macroeconomics is not about individual producers and consumers but how they behave as an aggregate. Macroeconomists want to smooth out the business cycle; which is the alternation of recessions and expansions. The business cycle can also be explained in behavioural terms. When things are going well people become overconfident and make poor investments thus leading to a downturn. During a downturn, they make calculated investments thus leading to economic expansion.

Macroeconomic objectives for an economy are economic growth, stable prices, full employment and external balances. While full employment might sound like no unemployment it actually means an unemployment rate at the natural rate of unemployment. There will always be some people between jobs due to frictional unemployment where people are looking for different jobs or perhaps even moving towards better jobs. Structural unemployment and cyclical unemployment, on the other hand, are due to shifts in the economy.

GDP or what you will soon remember as Y = C + I + G + NX. The formula is called the expenditure method of calculating Gross Domestic Product (Y). GDP is the final value of goods and services purchased in an economy and a common metric used to compare year-on-year economic growth. To calculate GDP we need to add the following:

- Consumption by households on services and goods.

- Investments in new business assets such as property, plants or variable ones such as inventory. Unintuitively, investments also include residential investment in new housing.

- Government purchases include government spending except those on transfer payments like welfare because that would get captured in consumption.

- Net Exports is the value of exports less the value of imports. This could play an important role because if an economy is importing a lot more than they are exporting it will be a negative number. A negative balance of trade occurs if a country imports more than they export. This could indicate they are incapable of producing enough to meet demand or that they are wealthy and consume much more than the country can produce.

All the above added together makes the GDP! Is it a good indicator? Maybe. Is it better than GNP (Gross National Product)? Not really. However, both these metrics don’t account for the sustainability of the growth and the depletion and degradation of natural resources and the environment. Cutting down a billion trees and selling them overseas will add a lot of growth to your GDP this year but there would be nothing to cut the following year. Some countries whose economies don’t rely on exporting raw materials or agriculture are more likely to attribute their GDP to innovation and technology.

Bonus: Something interesting but not intuitive behind understanding GDP is knowing one person’s spending is another person’s income. Therefore you can also calculate the GDP by adding up total factor income earned by households from firms through wages, profit, interest and rent. Likewise, calculating the final value of output from all goods and services produced by businesses would also provide the GDP. It has to be the final value otherwise you would be double counting.

Bonus Bonus: GDP per capita is a common metric used to measure the productivity per person. It is the GDP divided by a country’s population. However, it is not really an indication of the average wage earned; the GDP per capita, average wage and median wage can diverge since few people own a lot of wealth in many countries. For example, in the USA GDP per capita in 2018 was $54,541; the average wage (not household income) was $19,920 ($1,660 x 12).

Inflation! It is the increase in price level of goods and services. People with little formal economic knowledge have heard of the CPI or the Consumer Price Index. Maybe they have even accepted a pay rise based on the CPI (usually ~3%). I’ll explain later why this may not be a good idea. The CPI tracks the prices of a few household “essentials” and provides an indication of the price level by telling us whether things have become more or less expensive. Producers have their own index too, called PPI. To understand inflation, consider the purchasing power of the dollar and supply of money. High inflation is accompanied by low unemployment and/or government interference via controlling interest rates, tax rates or printing money. Why? As there is more money to go around, it starts losing its value or purchasing power. If somebody with ample money wants to secure a product, they can do so by offering more money. Similarly, if producers find that people are willing to offer more money, they will increase prices. Finally, since prices are increasing, employees will ask for higher wages for their labor, therefore, creating new price levels in the economy. If you understand inflation, you also understand deflation, which is the decrease in price levels. You can think of the in and de as increase and decrease (of the flation).

Inflation is not always a bad thing; the price level does not matter in the long term. If the prices of goods increase so do wages (in a perfect world) and other factors of production. It is the rate of change that matters. If inflation is erratic it makes money a less reliable unit of measurement, discouraging people from holding the unstable currency. Stability is also important because once price levels are established it becomes harder to move prices because prices are sticky due to contracts or because people are yet to realise the current price level. For example, someone with an employment contract for 12 months has already accepted the price for their labor. It’s fine when things become cheaper, but things becoming expensive can strain a person’s finances. There are also costs associated with inflation or deflation such as menu costs as firms must change listed prices and unit of account costs where someone may be unfairly taxed on gains due to inflation rather than real gains. It makes lending or leasing unreliable too. Erratic inflation would require adjusting interest rates frequently so it does not unfairly benefit borrowers or lenders.

Bonus: Why does the government prefer inflation over deflation? A bit of deflation every year incentivises people to save money as it is increasing in value. With a little bit of inflation though, people want to invest their money since it loses value every year. People investing their money in goods, businesses, new homes, creates economic growth. Growth via unnatural inflation due to government intervention may not be sustainable though. Cheaper access to money and loans allows uncompetitive firms to remain in the market and does not solve the root cause of a receding economy. Governments also tend to hold a lot of debt. Inflation provides a mechanism to reduce the real value of debt. A loan with an interest rate of 8%, with 5% inflation, would make the real interest rate 3% (money is worth less). As inflation increases, borrowers gain at the expense of lenders until correction or adjustments of the interest rate.

Unemployment actually has a natural rate of unemployment. It’s a magical number of ~4%. This is because everyone cannot be employed at all times due to frictional unemployment. If unemployment goes below the natural rate it actually causes inflation. If unemployment is around its natural rate, inflation may be attributed to government intervention. It is possible for economists to fudge up on both ends. They can overstate the true level of employment by counting people who are underemployed, marginally attached or discouraged therefore wrongly intervening with monetary policy (too early or too late). If unemployment remains stagnant or increases regardless of economic growth it can be because of technological breakthroughs or companies becoming more operationally efficient.

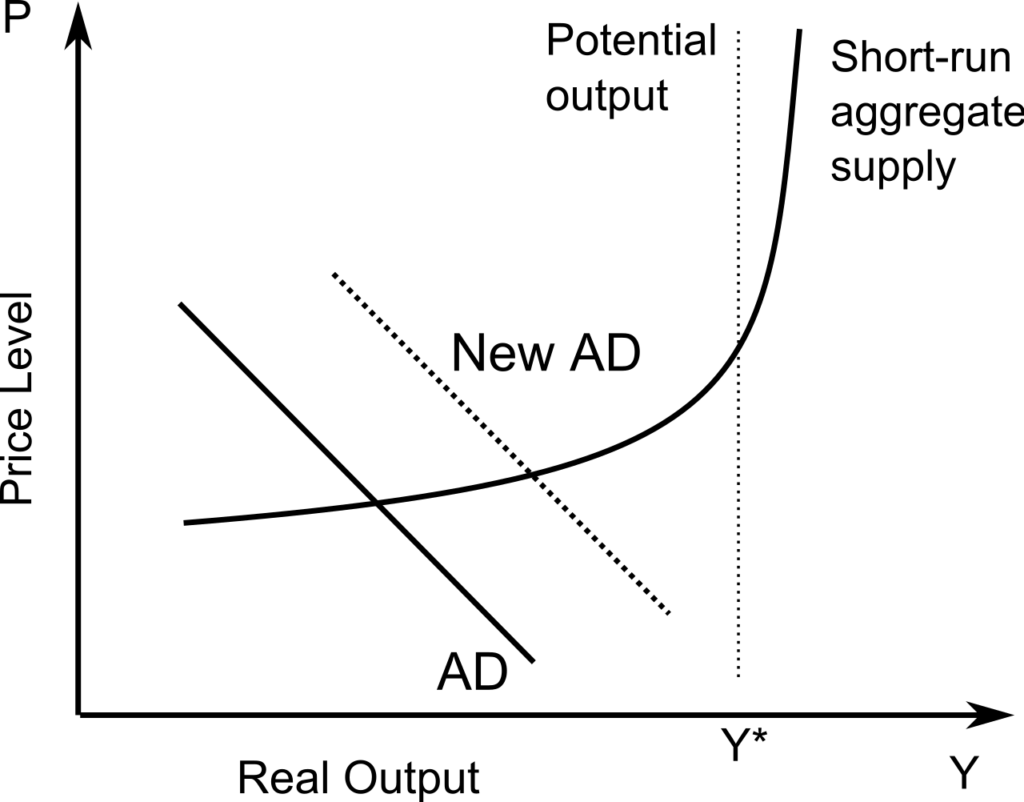

Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand! This is the supply and demand used by macroeconomists. In microeconomics, we care about prices and quantity. In macroeconomics, we care about the general level of prices (inflation) and everything an economy has produced (real GDP). We cannot use demand for a single product; instead, we use Aggregate Demand (AD) which is the GDP. The GDP is the sum of all the demand/expenditure. If you remember, it’s calculation is a sum of C, I, G, and NX so changes to those can shift the Aggregate Demand curve.

So the Aggregate Demand curve is the relationship of the price level and aggregate output demanded (the consumption of an economy relative to inflation). Aggregate Supply is the relationship between the price level and aggregate output supplied, rather than it’s consumption (remember people can still consume imports). AS does get a little more complicated.

There is the Short Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS) and the Long Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS). The LRAS is usually denoted by a straight line since it does not care about the price level. In the long run, we do not care about the price level, it is assumed to be at an optimal level. LRAS shows what the economy is capable of producing at the natural rate of unemployment. It is an economy’s natural capacity for output. SRAS is an upward-facing curve, it is what the economy is producing in the short term due to sticky factors of production such as prices, wages and capital. The SRAS cares about the price level because in the short term contractual wages, expectations and the price of inputs are not fully adjusted to the state of the economy.

Why care about LRAS when microeconomics does fine with just a supply curve? LRAS gives us an indication of where our economy is in its business cycle. If we’re producing and consuming far in excess of our natural level, we are in an inflationary gap. Likewise if we are producing and consuming far below our natural capacity, we are in a recessionary gap. When things are optimal we are consuming and producing right on the LRAS (AD and SRAS are at equilibrium on the LRAS). LRAS can shift, albeit slowly if we improve our natural capacity to create more output via technology, increased population and entrepreneurship. Once LRAS moves economies try to reach that new equilibrium where AD, SRAS and LRAS intersect once again!

FINALLY! Other things that influence how and when we get to macroeconomic equilibrium are monetary and fiscal policy. Monetary policy is government influencing the money supply via interest rate cuts, quantitative easing or some other scheme. Fiscal policy is the government investing in infrastructures such for the industry to scale in the future. Fiscal policy is ineffective because by the time bills pass and roads, railways or the NBN gets built an economy might not be in recession or have the same infrastructure needs. Monetary policy is ineffective because it does not fix the root causes of a poor economy and allows inefficient firms to stay in business, thus in the long run it only increases the price level. John Maynard Keynes who had an important role in popularising these policies used to say in the long run we’ll all be dead. Good luck.

Interesting resources to study:

Economics: A User’s Guide – Ha Joon Chang

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics – Richard Thaler